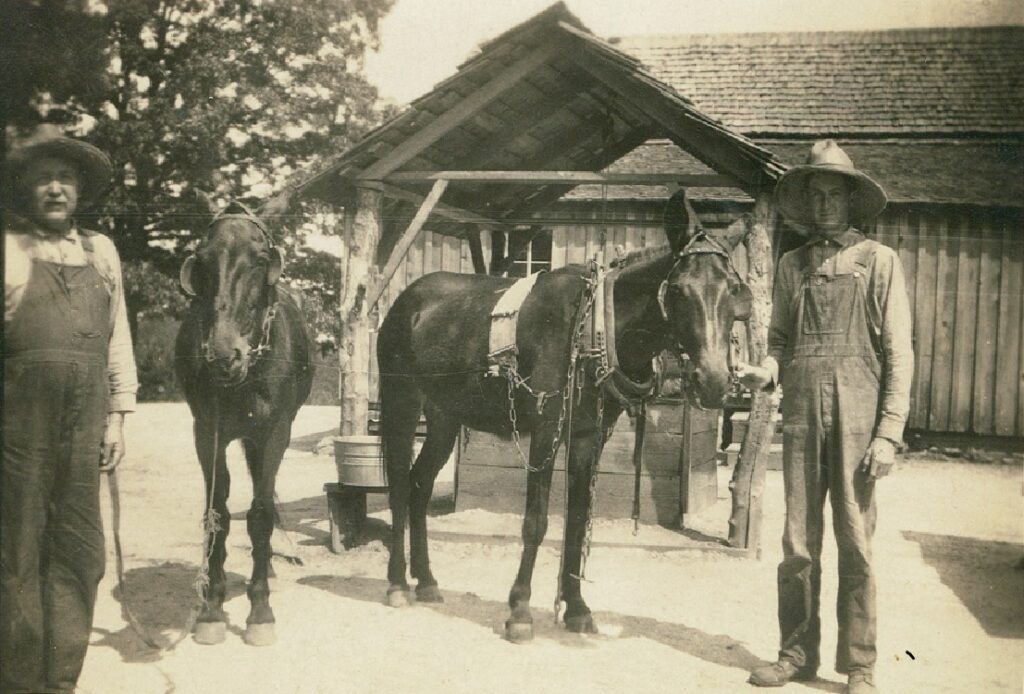

The other day I was given a mule collar by an anonymous friend. I polished it up a bit, brushed off the excess stuffing that had leaked out, and hung it in a place of prominence on the wall of the carport.

Although it has obviously been years since it touched a mule, I can look at it and conjure up the sweaty smell of a mule after a hard day’s plowing, as he patiently stands for the unhitching, then whirls away as soon as the bridle is removed to hurry to wallow in the dusty place behind the barn.

Webster says a mule is “the offspring of a donkey and a horse; especially, the offspring of a jackass and a mare, as distinguished from a hinny.” A more detailed description would include the fact that a mule, useful beast though he may be, can strain the religion of the most pious man who ever lived.

Let us now take a look at some memorable mules I have known.

First, there was Old Hat. (Please don’t ask me why, but it is mandatory when referring to mules that the name always be preceded by the word “old”.) Old Hat was a small red mule who had as much intelligence as any mule of my acquaintance, but she was mean about her ears. After a previous owner or two had been de-toothed trying to shear her, a method was devised whereby her head was chained or roped to a sturdy root or stake, making movement of her head impossible.

She pulled the first plow I ever walked behind — a Georgia Stock, center-furrowing corn. It was thought I couldn’t do too much damage there, but in the winding rows of those northwest Alabama hills she started taking advantage of my inexperience and cutting across the curves instead of swinging out as she should have (and she knew perfectly well to do) to make the plow run where it was supposed to.

Daddy, in the next terrace down the hill, noticed this and gave her a sound thrashing, wiped my nose, told me it wasn’t seemly for a seven-year-old to use that kind of language, and we went back to plowing, and she went around the curves from then on the right way, like a streetcar on its tracks.

Her teammate, old Bill, was one of those nervous mules, a fast stepper who minded instantly. You’d better be dang sure you wanted to “gee” before you told him, because he’d “gee” — right then. Of course, he wasn’t ideal for some jobs, like pulling a vibrator distributor, for example.

The faster he’d go, the louder it’d get, and the louder it’d get the faster he’d go, and if you said “whoa,” to try to start over again, he’d stop so suddenly you’d fall over the plow handles. And woe be unto you if your sunhat (everybody wore sunhats) blew off while you were plowing him. You could plow up the whole Ridge Field in five minutes, although not necessarily in the planned, Extension Service-approved manner.

Uncle Kelley was unfortunate enough to own old Ider. Fred, his hired hand would sometimes spend a quarter-hour trying to bridle her. Just as he’d almost get the bridle on, she’d change ends, and since it was the other end he wanted the bridle on he’d start coaxing. “Nice old Ider. Sweet old Ider. ‘Atta girl, just stick that pretty nose around here. Sweet old Ider.” Well, that would go on for a while (and Kelley swore it was true, because he’d hide and watch this performance, occasionally) until she’d finally relent and allow him to get the bridle on her. Then, he’d grasp the reins firmly in his hands, look her sternly in the eye, and say, “Huh! Think I’m scared of you, don’t you.” She’d never say a word.

Also, there were Uncle Kent’s running-away mules, Dock and Ader, which no man alive could hold once they made up their minds to run, which was anytime they were hitched to the wagon in stop-and-go situations like hauling wood or hauling corn from the field. You could just maybe make them go in a circle for a while till they tired of the sport. Looking back on it, Uncle Kent plaintively asks himself why he didn’t just shoot ‘em and borrow money for another pair.

Oh, I could go on, but I might get mad, just thinking about it, and say something in front of the children, you know. And a 10-year-old up the street saw my mule collar and said, “Oh, I know what that is; that’s a horse shoe!” Another one thought it was a life preserver. What do they teach kids these days, anyway?