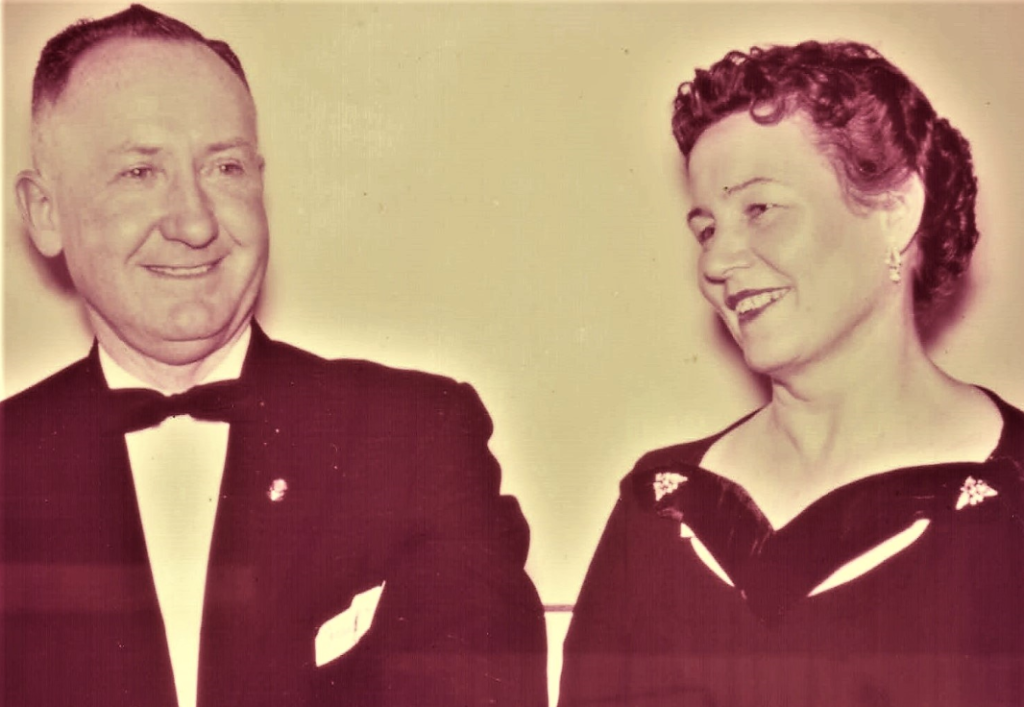

Prentice Sanders and Edna Boman Sanders

(Note: “Daddy” in this story is Prentice Sanders, son of James Marshall Sanders and Emma Springfield. “Mother” is Prentice’ wife, Edna Boman Sanders. The other characters are family friends.)

_____________________________________________________

We got to talking about funerals the other night. Somebody brought up the famous New Orleans funeral marches, and we kept on till we got to country funerals and the fascination with them–over and above the natural sympathy–of country folks, especially those of a generation ago.

I had to do a little looking up about funeral customs to satisfy my curiosity. I found that our basic funeral customs came from the Romans, who brought them to England when they invaded that country in the year 43, customs like wearing black, walking in procession, and raising a mound over a grave, which were later passed on to our country, where regional and denominational variations were added as time passed.

Daddy and Mother used to sing at funerals. Hundreds of funerals. I don’t know exactly how it got started. They both grew up in the center of the all-day-singing, singing-school belt and became respected regulars at the singings in the area, and at various times they teamed up with other singers to form quartets at these singings.

Somewhere down the line, somebody asked them to get together a quartet to sing for a funeral and they did and somebody else asked them to and they did, and before anybody realized it, it had become a regular thing. Along in the late ‘30s, through the ‘40s, and on into the 50s, whenever anybody died within a radius of ten or so miles, one of the deceased’s relatives would call Daddy or one of about six or eight others and say they wanted them to sing at the funeral and that was it. They would.

Daddy’d work up till the last minute before time to get ready, then drop everything and get Mother and a couple of other singers out of a pool consisting of Lester Crowder, Bradley Wheeler, Otis Williams, Junie Harper, Uncle Grady and a few other singing types, and they’d head for Bethlehem or Nebo or Oak Hill or Pine Springs or Mt. Harmony or Shake Rag or Pin Hook or wherever the service was to be held.

The ritual was fairly consistent. After a while, they knew most of the preachers who would be likely to be officiating, so they didn’t have to have many preliminary instructions. Usually the family would have one or two songs they’d especially want sung–invariably the saddest songs imaginable, designed to purge every last tear and moan out of the survivors’ systems. After the preacher had intoned a few appropriate words, he’d indicate that it was time for Daddy and them to sing. They’d quietly and quickly set the pitch with the always present pitch pipe and start singing. Sometimes there’d be another song or two in the church house, and perhaps, one out at the graveside.

Down through the years they accumulated quite a stock of anecdotes about happenings at funerals–about the times when the song would be pitched too high and Bradley’d be standing on his tiptoes with his neck chords standing out, trying to reach the high notes and about the extremes in weather, from the tortuously hot, muggy times to the deluges to the bitter cold days when the wind would come whipping over the burial grounds in a manner calculated to freeze the vocal cords–and all other parts–of the singers and everybody else, while the preacher would grind on and on and on, exhorting and preaching to a helplessly captive audience–and about the time the wasp got up Junie’s britches-leg at one of the most emotional moments. Junie got pretty emotional himself. His range broadened considerably.

Nobody kept records. Nobody knows how many funerals they sang for. For a couple of decades they probably averaged at least three funerals a week. Of course no pay was asked for or accepted. Most times they weren’t even thanked. But when Mrs. Mills rang a long and a short and it would be somebody asking them to sing, they’d sing. It was just something you did.

I don’t know who does that now, if anybody, since most of the old singers have more or less retired. People used to flock to funerals, to honor the dead, of course, but also to see other people and renew old acquaintances. I don’t think as many non-family people go now, but funerals are still the biggest news around in rural areas.

Easily the most popular program on my hometown radio station, at least for the 50-or-over set, is the death announcement program at mid-morning, sponsored by the local funeral home, in which the announcer, in the dulcetest tones he can muster, tells that Mr. or Mrs. (pronounced “miseries”) So-and-So “passed away” at such-and-such time and place with services to be held where and when. And listen again tomorrow when your friendly funeral home will bring you the latest death announcements.